畳

Tatami

Tatami (畳) is a soft mat floor covering which is used in traditional Japanese style rooms and dojo. They can also be seen in places and rooms such as inns, restaurants, temples, and tea houses.

When entering a tatami room, it is custom to remove shoes and slippers to prevent damage to the mats.

— Construction

They are shaped like a 2:1 rectangle. Generally, tatami dimensions are about 91 cm x 182 cm x 5 cm, but the sizing may vary by geographical region of Japan, and type of room it is in.

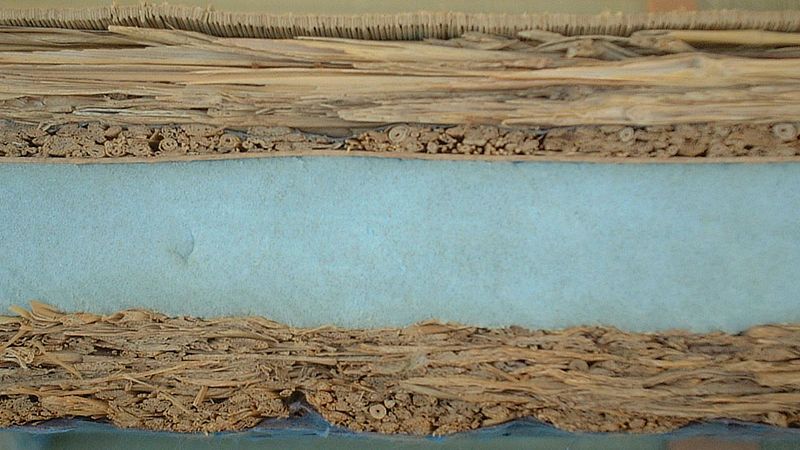

The core, tatami-doko (畳床), traditionally was made from rice straw, but nowadays, it is typically made from compressed wood-chip boards or polystyrene foam. The change is a result of a reduced supply of rice straw and concerns of mite and mold infestations.

Over the core, tatami-omote (畳表), is the tightly woven grass covering called igusa (藺草). Although not required of all tatami, they are often constructed with a cloth border, tatami-heri (畳縁) on all sides.

In the average home, the cloth of the tatami-heri is black, navy blue, or brown, while in temples and mansions, they are made with colorful silk. They are woven to create figured patterns. Often, gold and silver are included in the designs.

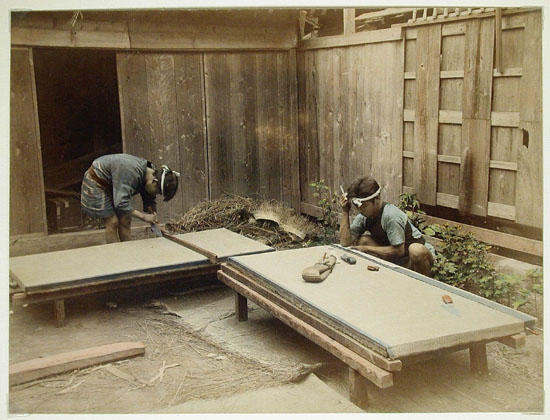

— History

Tatami didn't come about until the Heian period, and they were far different from today's tatami as they were simple cushions, sleeping mats, and straw mats for sitting on.

The word tatami is derived from tatamu (畳む), meaning to fold or pile. This is because the earliest tatami was folded and stored away when not in use.

During the Heian period, when tatami was created, they were a luxury used by only the most influential aristocrats. In their residences, the floors were mostly wooden, and the tatami would be taken out for use. The lower classes only had simple straw mats to cover the dirt flooring of their homes.

During the Kamakura period, tatami began to be laid out over small rooms. Although it was still considered a luxury item that commoners could not get a hold of, high ranking samurai and priests began to use them in their own homes.

The Muromachi period marked the rise of the mats being laid out closely together to cover entire rooms. Rooms that were completely spread with tatami began to be known as zashiki (座敷). The mats themselves were called shiki-datami (敷畳), to contrast the single mats called oki-datami (置畳), meaning "single mat-like cushion."

One could quickly recognize someone's social status based on the thickness of their oki-datami, as well as the colors and patterns of the tatami-heri.

For sleeping purposes, the mats used by nobility and high ranking samurai were called goza (茣蓙), while common classes used simple straw mats or loose straw to sleep on.

Tatami began to reach the common population around the end of the 17th century, during the mid-Edo period. Usage grew, and eventually it became standard in farming houses during the Meiji period. Tatami were standard in just about every house until after WWII, when westernization grew rapidly.

Today, homes have very few tatami floors, although it is not uncommon for a home to have a single room with tatami flooring. These rooms are now called washitsu.

— Size by Region

Because tatami are created in standard sizes, it is common for square-footage of a house to be measured in number of tatami mats.

Ones made in Kyoto are called kyouma-datami (京間畳), and are sized as follows: 95.5 cm x 191 cm.

Ones made in Nagoya are called ainoma-datami (合の間畳), and are sized as follows: 91 cm x 182 cm.

Ones made on Tokyo are called edoma-datami (江戸間畳) or kantom-adatami (関東間畳), and are sized as follows: 88 cm x 176 cm

Ones used in the countryside are called inaka-datami (田舎畳), are the same size as ones made in Tokyo.

— Layout

There are rules for how to lay down tatami.

The are two main ways that they can be laid down: in shūgijiki (祝儀敷き) or in fushūgijiki (不祝儀敷き).

Shūgijiki are arranged to create 'T's, while fushūgijiki are arranged to create '+'s. Nowadays, fushūgijiki is thought to bring bad luck, so shūgijiki is primarily used.

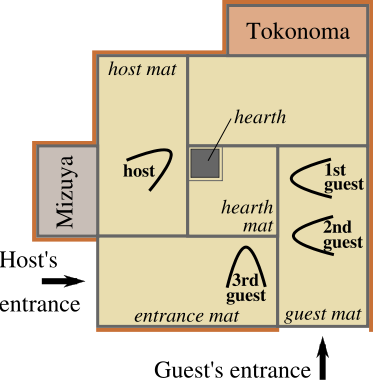

— In Teahouses

Tatami in chashitsu have special names. The mat that the host sits on is called shudatami (主畳), temaedatami (点前畳), or dougudatami (道具畳). The tatami from where the host enters is called fumikomidatami (踏込畳). If a guest is a nobleman, the mat they sit on is called kinindatami (貴人畳). If the guest is ordinary, the mat they sit on is called kyakudatami (客畳). The mat where the irori is located is called rodatami (炉畳).